I had the pleasure of attending and speaking at the recent Taxonomy Boot Camp that is part of the overall KM World Conference held in Washington, D.C.

There were many promising solutions that provide the capability for organizations to understand and organize their unstructured information, whether that information is in the form of documents, news stories, or social media. Attendees were interested in the general topic of classification and how to approach it.

While there is a great deal of interest in classification and some examples of successful implementations, uncertainty remains regarding the technology behind it and how to align capabilities with specific problem scopes. In general, the confusion is a result of three factors:

- Overlap of related terminology describing techniques, methods, and concepts;

- Myriad of technologies to choose from that provide different options for addressing classification challenges; and,

- Strengths and weaknesses of these technologies in addressing specific problem sets.

Ultimately, we are faced with more and more information that basic search technology cannot find or retrieve, and the way we describe and reference this information is constantly evolving. As a result, organizations everywhere tend to take the most risk averse position available – they horde it all. When looking at how to organize all of this data, where does the organization begin?

Improving information management requires better metadata. You can either tackle it as it’s coming in or on-demand when it is necessary to find something. The challenge is always with accurately describing information that has high relevance to the audiences who need it. In a study by Bell Labs in the mid-80’s, the most common approach of assigning Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) with the task of describing information results in a high retrieval failure rate – up to 85 percent of attempts to use metadata to find information resulted in not retrieving the most relevant data. In the end, the ability to apply a broad set of metadata and “aliases” such as synonyms meaning-based derivatives is the best-available approach.

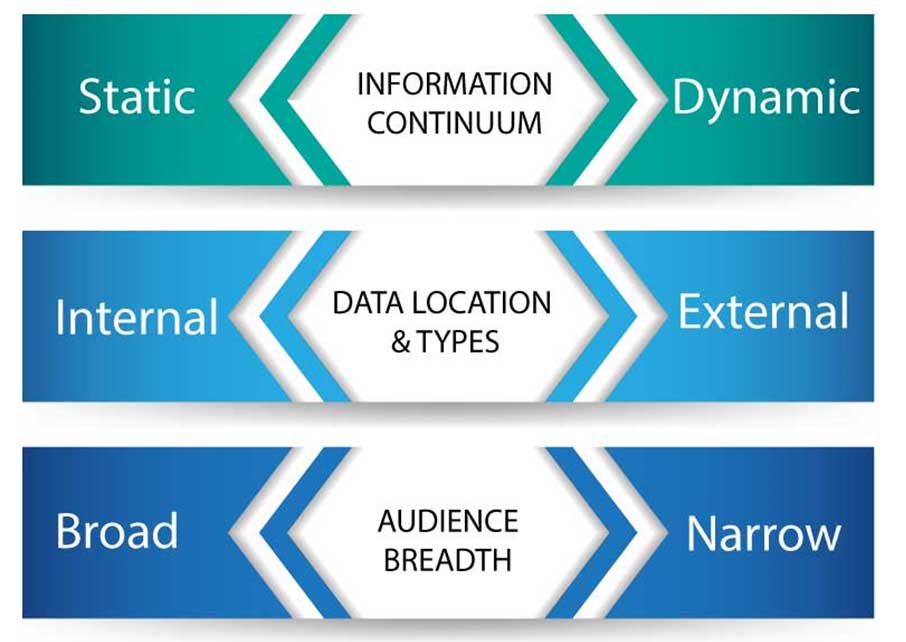

When tackling the metadata assignment challenge, many information management approaches exist for any project, but I typically boil it down to three:

- Information: the nature of the information–static to dynamic;

- Data Location and Types: the place where data is created and curated; and

- Audience Breadth: meeting the needs of different audiences from broad to narrow or very specific audiences.

Each of these can be thought of as as part of a continuum. Take, for instance, the nature of information. Is it dynamic and constantly changing or is it fairly static? Do the uses for the information change over time or do they also remain constant? The answer to these questions will have a big factor into how you approach your metadata breadth as well as how often you refresh your metadata. The more dynamic, the broader your metadata needs to be. For the second continuum, if you find that a lot of the information is created or curated outside of the organization, it means you have less control over how it is used and less ability to train users on retrieval tactics, which also means that you need to expand your metadata to ensure that retrieval will be more successful. For the last continuum, the breadth of your audience, whether internal or external will affect the range of metadata applied. If you only need to service one department, it is probable that metadata can be constrained to specific use cases. If multiple departments are involved or if there are stakeholders outside of your organization, then there is a higher likelihood that each stakeholder will have their own lexicon that needs to be incorporated into your metadata plan.

All in all, it is not terribly difficult to give your project a much-improved chance of success with a little upfront work on understanding the types of information, the place where that information resides, and the audience. But in all cases, the project is always a work-in-progress due to the changing nature of information and the way it is used.